Land Use and Climate Change: What You Need to Know

by Sydney Welter (Director of International Partnerships and COP25 Delegation Co-Lead)

Since the emergence of sedentary agriculture, human welfare and responsible land management have been inextricably linked. The importance of responsible land use has received renewed scientific, political, and media attention during ongoing crises like the burning of the Amazon rainforest. Mitigating climate change and adapting to its effects will require drastic changes to our existing land-use practices and food systems.

WHAT IS LAND USE AND HOW DOES IT RELATE TO CLIMATE CHANGE?

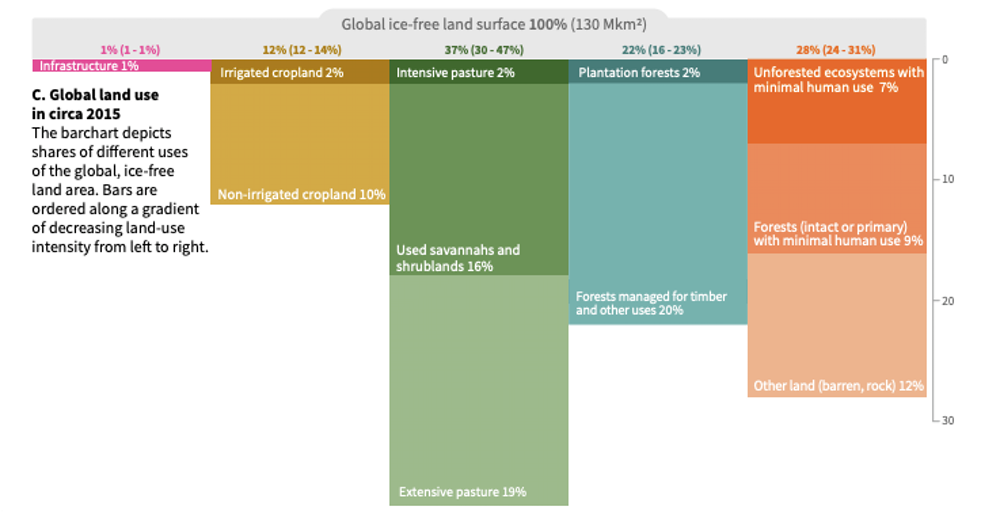

Land use is the way we manage our natural environment, or more simply, how we take up space on Earth. Of the ice-free land surface on the planet, only 28% of land is mostly unused by humans. The rest of the planet’s ice-free land surface breaks down as follows: 22% forest used by humans (e.g. for timber), 37% grassland used by humans (e.g. for pasture), 12% cropland, and 1% infrastructure.

This land use by humans contributes significantly to climate change, representing 23% of total net anthropogenic (human-caused) GHG emissions (IPCC, “Summary for Policymakers”). This contribution to climate change results from both the loss of GHG sinks through land-use changes (such as deforestation) and the addition of GHG sources through land-use changes like increasing industrial agriculture.

Uses of global, ice-free land area (IPCC, “Summary for Policymakers”).

In addition to contributing to climate change, land use is also affected by climate change. As the Global Mean Temperature rises, so does our risk for desertification, land degradation, and food insecurity (IPCC, “Summary for Policymakers”). This relationship between climate and land is thoroughly explored in “Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems”, which was released this past August. The importance of this report is underscored by the ongoing burning of the Amazon rainforest for industrial agriculture--a perfect example of both destroying carbon sinks and introducing additional emissions sources through industrializing the land. The rise in global mean temperature also drives the desertification of the rainforest, increasing the cascading effect of the intentional fires and further devastating biodiversity and indigenous people’s lands, including the loss of land available for sustainable subsistence.

WHAT ARE THE SOLUTIONS TO THE FEEDBACK BETWEEN LAND USE AND CLIMATE?

Numerous land-based solutions can mitigate GHG emissions and ensure long-term use of our natural resources. Sustainable agriculture practices, such as regenerative agriculture and farmland restoration, can ensure prolonged use of nutrient-rich farmland and manage risks like soil degradation.

Sustainable grassland and forest management practices, such as silvopasture, managed grazing, and disaster risk management can protect against soil degradation and limit events like harmful forest fires. Ecosystem conservation and afforestation and reforestation offer carbon sequestration to lower net GHG emissions.

Many land-use solutions align with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals to improve conditions for those most impacted by climate change and poverty. Sustainable agriculture is not new--it has been practiced for thousands of years by certain populations. Indigenous land management and female smallholder farming provide more sustainable land use, due to the smaller scale and use of regenerative agriculture practices, such as swidden agriculture, that restore soil nutrition. Protecting these lands and mobilizing resources for female farmers and indigenous peoples will simultaneously aid those communities and our planet (Project Drawdown and IPCC, “Summary for Policymakers”).

Signs for indigenous land control (David Tong).

Indigenous-led protest at COP25 (David Tong).

HOW DO WE ENACT THOSE SOLUTIONS?

Mitigating both the impacts of land use on climate change and the impacts of climate change on our natural resources will require a massive overhaul in the way our food systems operate. Industrial agriculture, which contributes to deforestation, soil degradation, water and air pollution, and GHG emissions, is not sustainable.

Where possible, individuals should reduce their meat intake and purchase food from smaller farms with sustainable practices. However, food systems issues make this effort difficult for many. For example, in the United States, the food desert crisis and the eradication of small farms through industrial consolidation leaves many Americans struggling to access sustainably-farmed, plant-based foods. The greatest responsibility lies with the governments currently beholden to corporate interests over the needs of ordinary people. Governments must commit to regulating industrial agriculture and make sustainable and nutritious food more accessible to their people. The public and private sectors must mobilize finance to aid to implement sustainable solutions. Finally, we must radically commit to preserving existing land and returning land to wilderness, smallholder farming, and indigenous management.

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

“Climate Change and Land: Summary for Policymakers,” IPCC, 7 Aug 2019